Just Back From…Greenland on Silver Wind

From 35,000 feet, the granite-spiked coastline looked like gorgeous, random fangs. The sea was studded with polka dots — icebergs big enough to see from six miles aloft. Freeways of ice slinked around the granite on a relentless march toward the sea. And as we flew west, the white plain of the immense ice sheet — larger than all of Alaska — was dimpled with nearly translucent blue lakes, gleaming like pale sapphires.

I hope your first glimpse of Greenland is as stirring as mine.

The weather gods don’t always deliver clear summer skies here, but when we landed at Kangerlussuaq, Greenland’s gateway, we were greeted with cloudless skies and air so clean and crisp I gulped with glee. And yes — there was green.

The chartered plane was flying passengers to Silversea’s Silver Wind, our home for the next week for a cruise along Greenland’s west coast. Our journey would stay mostly north of the Arctic Circle, the latitude that unofficially defines Earth’s polar regions. North of this point, the sun doesn’t set during the summer solstice; at winter solstice, the sun doesn’t rise.

Many of us aboard the flight weren’t quite sure what we’d find. A blinding snowstorm? Life beyond all that ice? Residents who wouldn’t live anywhere else?

Here’s what I discovered on my first expedition cruise to Greenland, where I had traveled previously on a land trip.

The lay of the lands

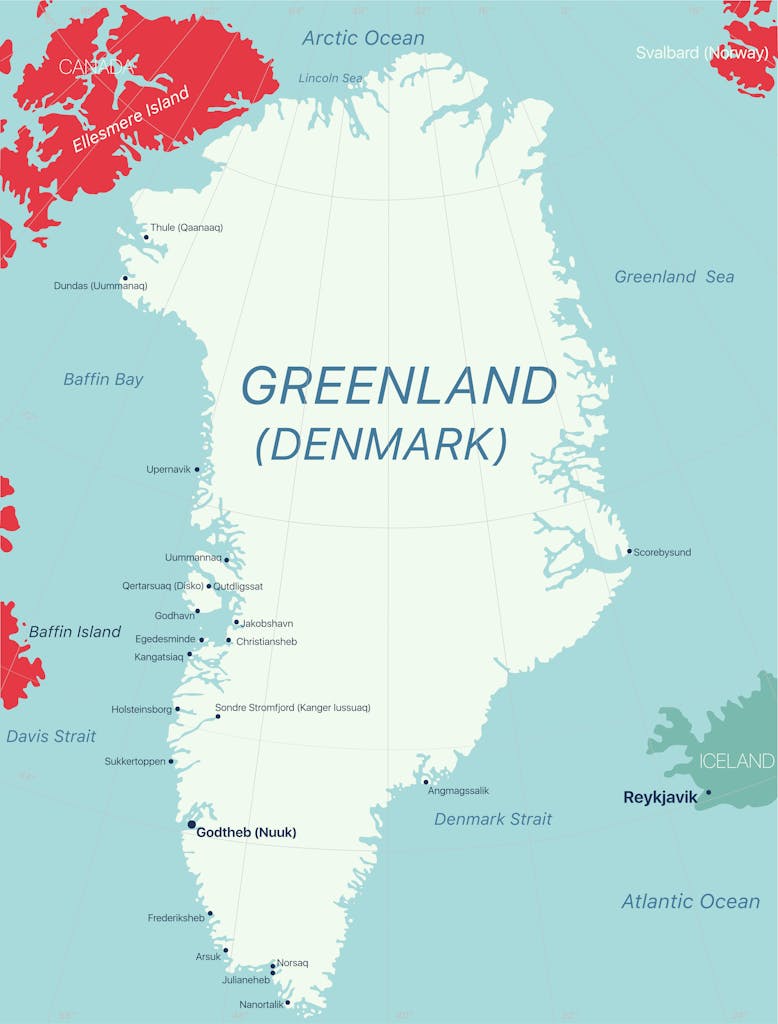

A cruise to the Arctic regions usually doesn’t mean only Greenland. Many cruise itineraries will touch on more than one of four destinations: Iceland, Svalbard, Canada and Greenland. But my cruise was sticking to Greenland.

At more than five times the size of California, Greenland is the world’s largest island. This autonomous constituent of Denmark is home to 56,000 people, which makes it the least densely populated land mass in the world. Most of the population lives almost exclusively along the west coast.

Our flight landed well before noon and thus before the ship was ready for boarding, so we headed by bus to explore Kangerlussuaq, venturing along a sandy track to a roadside viewpoint opposite Reindeer Glacier, about 16 miles inland. White hovered on the horizon like a cloud creeping over a ridge; behind it lay 300 miles of uninterrupted ice sheet that looked as though it was oozing across recumbent hills at an imperceptible speed.

On the way back, a half-dozen muskoxen grazed in a field, scooting away as we stopped to snap a photo. Below my feet were cotton ball-like flowers, a type of sedge common in polar regions.

Introducing Silver Wind

Members of the expedition team met us at the dock, then ferried us a couple of minutes across Kangerlussuaq fjord in Zodiacs to Silver Wind. In my balcony suite, a bottle of Champagne chilled in an ice bucket, and a red Silversea expedition jacket awaited on my bed. At 240 square feet (plus the veranda), these are decadent digs for a solo traveler, and with such amenities as a walk-in closet, plush bedding, proper reading lights and a table suitable for in-room dining, I knew the coming week would be comfortable.

I spent that afternoon acquainting myself with the ship, which launched in 1995, the second in the Silversea fleet. During the pandemic, Silver Wind was converted from a classic cruiser to an expedition ship, and I was curious to see the adaptations. Most obvious is the fleet of 24 Zodiacs and 10 kayaks stored on aft decks and three mounted cranes to haul the craft in and out of the water. A new “ducktail” on the rear of the ship improves stability in rough water. The hull has been reinforced with a steel “ice belt” that extends above and below the water to protect the ship from an ice strike, and the new, thicker bulbous bow protrudes from just below water level to make the ship even more seaworthy in icy water.

Silver Wind was slightly larger after its conversion, but the number of guests decreased by two dozen to make room for the crew of expedition guides for this group of 274 passengers. That made the guest-to-crew ratio about one-to-one.

I made my way to The Restaurant, where the menu promised house-made spinach ravioli, swordfish, a black angus and artichoke carpaccio, Malabar chicken and grilled Maine lobster. I tucked into a bright mesclun salad and the chargrilled swordfish, swaddled in olive oil and capers and perfectly seared. Sorin, my waiter, charmed, the wine flowed, and the clock ticked toward the first night’s briefing.

Getting down to the business of fun

“Welcome aboard this fast and furious trip through Greenland,” says Iggy Rojas, our expedition leader. The briefing, mandated by the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators, covered how to visit the Arctic responsibly. Polar bears were unlikely where we were headed, Rojas says, but he alerted us to the presence of rabies and told us to avoid touching any huskies.

We learned about the strict regulations that govern how Zodiacs are operated near glaciers. If we wanted to kayak, we were required to attend a kayak briefing the next day, no matter our experience level.

The smiling expedition team, more than two dozen in all, also took the stage. Each brought a unique talent that would enhance our experience.

Besides safety information, Rojas delivered an equally important point: “Be respectful of the local cultures.”

Silver Wind pulled anchor and began sailing down the long Kangerlussuaq Fjord. I settled onto my balcony and marveled at my good fortune. A veneer of clouds materialized, catching the last of the sun’s horizon-hugging gleam.

Small town, big ice

In the morning, we anchored off Kangaamiut, near the mouth of the Kangerlussuaq Fjord. The village is home to just a few hundred people, a number that has shrunk, I was told, as Greenlanders relocate to Nuuk, the capital.

I watched as some children headed to a building up the hill and asked one mother if they were on their way to school. No, she says; it’s a holiday. “Everyone is off hunting reindeer and muskoxen,” she says.

The village was expecting us, and one house was open for visitors to look at local handcrafts and taste some Greenlandic foods, including local prawns, minke whale blubber, dried cod and dried muskox. I later skipped a flensing demonstration — the skinning of a freshly caught seal, a major part of the Greenlandic diet.

Despite dour skies, rugged little Kangaamiut had lots of visual appeal. I clambered to a rocky overlook above town that offered a view in the other direction to the town’s cemetery, where rows of crosses lined up against a dramatic backdrop of spiky peaks.

Back aboard, our sea kayak briefing began with a lesson on Greenland, Canada and Alaska’s roles as the birthplaces of the kayak. “This is how people have been traveling here for a long time,” says Calle, our kayak instructor from Sweden. We would be paired in double-kayaks, Calle notes, and some previous experience was expected.

He tells us to think of the paddling as “more like a museum walk.“

“You’ll paddle for a bit to a certain spot and enjoy the place from the kayak,” he says. “It’s not a kayak race.”

An hour later, as we sailed up the Evighed Fjord, a lottery chose the first 14 guests to kayak , and I made the list. Time to gear up: a double layer of non-cotton socks, long underwear and pants, a double layer of shirts, hat, gloves and the red expedition jacket, plus the ship’s dry suit, kayak skirt, booties and life vest.

As a solo traveler, I joined Jenni, another soloist, who was on her first trip away from Australia after lockdown. Slipping into my seat, I was glad to share with someone of some experience. Within moments we were rewarded with a superb glacial encounter — sublime and peaceful, except for the calvings every few minutes that sent ice crashing into the sea, followed by a thunder-like crack that echoed across the fjord. All of us gaped from a safe distance.

Jenni invited me to join her for dinner at La Dame, Silver Wind’s French restaurant that comes with a $60 upcharge. We enjoyed attentive service even more than in the usual venues. Our meal started with martinis, caviar with buckwheat blinis, foie gras. Then came the lobster bisque, lamb chops, soufflés, fine cheese and more.

Greenlandic history and culture

Silver Wind called on Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, home to about 19,000 people, which makes it a bit smaller than Juneau. But it is one of the few Greenlandic communities that is growing. I had traveled to Nuuk 14 years ago and spent part of this cruise visit comparing the old part of town, where new buildings have sprouted, and the new suburbs, reaching a mile or more outside downtown. What once were dirt sidewalks are now paved; the grocery store I remembered stocked a surprising range of fresh items, such as avocados, lemons, mangoes plus a variety of fresh meats. (Seafood was a given, then and now.)

A highlight of my Nuuk visit was the Greenland National Museum & Archives. The extensive artifacts provide a broad overview of the island’s history and culture. One room is devoted to kayaks, some quite small. The Qilakitsoq mummies, a significant 1970s archaeological find in Greenland that shed light on the life of the Inuit five centuries ago, impressed me. The four beautifully preserved mummified bodies are respectfully sequestered from the rest of the exhibits.

On the fourth day of the cruise, we sailed into Sisimiut, Greenland’s second-largest city. The town of 5,600 sits amid rocky peaks , but it’s also noteworthy for being the southernmost settlement in Greenland where huskies are permitted. (Greenland allows them only north of the Arctic Circle and on the east coast, partly for health reasons). Barking and howling were omnipresent.

Our day in Sisimiut paled compared with what was ahead, Iggy promises at the nightly briefing. “Tomorrow will be one of the most fantastic days as we visit Ilulissat,” he says. “It is a place so incredible it is a UNESCO World Heritage site.”

We also would visit one of the most productive glaciers on the planet, the one thought to have calved the iceberg that doomed the Titanic.

Staring into the future

On my previous visit to Greenland, I had heard that Ilulissat, 350 miles north of Nuuk, was Greenland’s star attraction. I didn’t make it last time, but now Silver Wind was inching into Disko Bay, which the town overlooks.

Ilulissat sits at the mouth of a fjord, a 2,000-foot-deep undersea valley carved by glaciers. About 30 or 40 miles inland is the face of the Jakobshavn Glacier, a river of ice so hyperactive during the spring and summer that it is said to produce more than 25 billion tons of ice annually, more than any other glacier in the world.

Because the glacier can advance hundreds of feet a day in summer, the larger icebergs calved from the glacier can measure hundreds of feet across and as much as a half-mile high. The fjord was choked with ice, which begs this question: Why doesn’t the ice just float off to sea? It took a boat ride to the mouth of the fjord to learn the answer.

We had three options for the day, but our 10 hours in Ilulissat would allow only enough time to select two excursions. One was a helicopter to the glacier, which was an additional fee, so I stuck with the included tours. First up: a boat cruise into the fjord. A series of local boats, some holding as few as four passengers and an expedition guide, lined up to ferry us through the ice. A few minutes after leaving the dock, we were gawking at white and pale blue bergs.

The captain explains how the glacier reached what is now the mouth of the fjord a few decades ago. The rubble and debris the glacier scraped away created a moraine, an undersea mass rising to within 600 or 700 feet of the surface — just tall enough to impede larger icebergs from flowing into the open sea. The icebergs we saw rising 100 feet or more above water presumably reached more than 600 feet below the surface. (About 80% of an iceberg lies below the surface.) Until they shrink enough to glide over the mass, they’re stuck in the fjord.

My afternoon tour was a guided hike to a viewpoint above Disko Bay, but I broke away from the group to wander ahead through town and on to a trail that led to the mouth of the fjord so I could take in a view of the trapped ice. For the last mile, a pair of huskies accompanied me, running ahead as if to urge me on. When we arrived at the epic vista, I wondered whether dog brains could imagine the sheer enormity of a place that was formerly, to me, a dot on a map.

Greenland’s ice sheet is ground zero for climate change, and the Jakobshavn Glacier in particular is expected to create a global rise in sea levels. If 3.3% of the ice sheet melts by the year 2100, according to current projections, the sea will rise 10 to 12 inches.

Our evening sail out of Disko Bay was calm enough that I ventured up to the pool deck where Hot Rocks, the ship’s al fresco-only steakhouse, sat poolside. On some Arctic evenings, this was not the ideal place for a meal. But tonight, Jenni was there cutting into a tasty-looking fillet, and she invited me to join her. A waiter immediately brought a blanket to cover my legs, though the overhead heat lamps were almost enough to keep me warm. I ordered a baked potato, along with a New York strip, and soon a slab of searing rock, maybe 6 inches across, arrived, along with the raw steak.

I tell Jenni that getting the cut cooked to my liking has been spotty on previous visits to Hot Rocks. She asks how I like my steak — medium rare is good for me — and she tells me to time it.

“Three minutes each side, no more than four, then slice in to see if it’s right,” she says. I set my iPhone timer, and her instructions worked perfectly. The simple meal, accompanied by views of icebergs left and right, was one of the best of my cruise.

The day’s most amazing sight came a couple of hours later.

About 11 p.m. I ventured out to my balcony to enjoy glints of orange that the slowly setting sun cast onto a sky of cotton puffs. I grabbed a few photos and went back inside to take care of some work, but as I continued to glance out, I realized the sky was getting better. For more than an hour, I ventured back to the balcony every two or three minutes to shoot another photo, thinking the sunset had reached its peak.

The pinnacle for me was at 12:10 a.m. The sun was just above the horizon, and the clouds reached a persimmon-hued brilliance, separated by patches of deep blue sky, and dotted in the foreground by icebergs, which glowed blue. It was the sunset to beat all sunsets

Somersaulting bergs and diving flukes

Early the next morning, we slinked quietly into Uummannaq. I had gone to bed disappointed that I hadn’t made the cut in the nightly kayaking lottery. When I awoke to a view of this small island — a soaring peak, speckled with colorfully painted houses on its broad shoulder and ringed by icebergs — I decided to visit the expedition office to check for no-shows. There were two, Calle tells me. He wasn’t keen on my kayaking solo, so he corralled a staff member to join me. We jumped into our gear quickly and met in the mud room for a transfer into Zodiacs that ferried us to the kayaks.

The bay fronting the island was peaceful — no wind or waves disturbed the surface as we paddled north, icebergs on all sides. Calle advises us to assess the height of each berg and stay twice as far away in the water. Just after passing one garage-sized hunk, we witnessed the ice slowly roll over, perhaps unbalanced by the ripples caused by our kayak. The berg flipped from one side to the other, and back again, and over again, a show that went on for several minutes as it rebalanced.

Then, Calle pointed across the bay. “A fin whale,” he says. I heard the exhale, but my back was toward the sighting, perhaps a half-mile away, and I didn’t see it. Moments later I heard the unmistakable exhale of another whale, again fairly distant, but this time the sound came from in front of me, and I could see the telltale plume of mist. My instinct was to start paddling toward the creature.

“If you paddle toward the whale,” Calle says, “there’s a good chance he’ll come up behind us and you won’t see him again.”

Thus began what I can best describe as an exquisite meditation. All of us floated in the bay, the nose of our kayaks pointed toward where we had seen the whale, which continued to surface and which Calle determined was a humpback.

Although we avoided paddling, a nearly imperceptible current carried us toward the whale, and soon we got close enough to realize there were two whales, one much smaller. “It’s a mother and calf,” Calle says.

For about 40 minutes, we hardly spoke, watching the pair feeding along the island’s shoreline a few hundred feet away. Every couple of minutes the mother would go for a deep dive, her fluke pointing to the sky before gracefully slipping into the depths.

An early sail was scheduled for that afternoon. Silver Wind’s captain planned a scenic cruise through Uummannaq Fjord, and it coincided with the clouds giving way here and there, allowing slivers of blue sky. Against a backdrop of rugged mountains, the ship glided by icebergs big and small. The distance was sometimes close — we were definitely not keeping the breadth advised for the kayaks — but I trusted the ship’s ice-detecting sonar equipment that kept the bridge aware of what we could not see.

On our last full day, we dropped anchor off Itilleq, a settlement of 89 people. As we boated to the village dock, a light drizzle enveloped us. Other than a quaint, well-kept church, where heating warmed all who came in for a peek, it didn’t seem as though there was much to see.

But among the dozen or so residents who emerged shyly to greet us were three teenage boys. In the middle of the village was a soccer field. Someone from the expedition staff said, “I think we can get a game going.” An informal soccer match broke out, eventually attracting more than a dozen playing cheerfully in the drizzle.

I must have more

A week before, when expedition leader Iggy Rojas greeted us, saying, “Welcome aboard this fast and furious trip through Greenland,” I didn’t fully appreciate his words, but now I understood.

I didn’t expect to leave Greenland breathless, and if there was a shortfall of our seven-day journey, it’s that there’s much more to see in a place that’s rich in sightseeing, culture and adventure. The ship has Jacuzzi tubs and a pool, a spa and gym, but who had time for any of those? Lectures by expedition staff, whose backgrounds included ornithology and glaciology, left me wanting more. And climate change? There was so much more to learn.

That and the spectacle that is Greenland will bring me back.