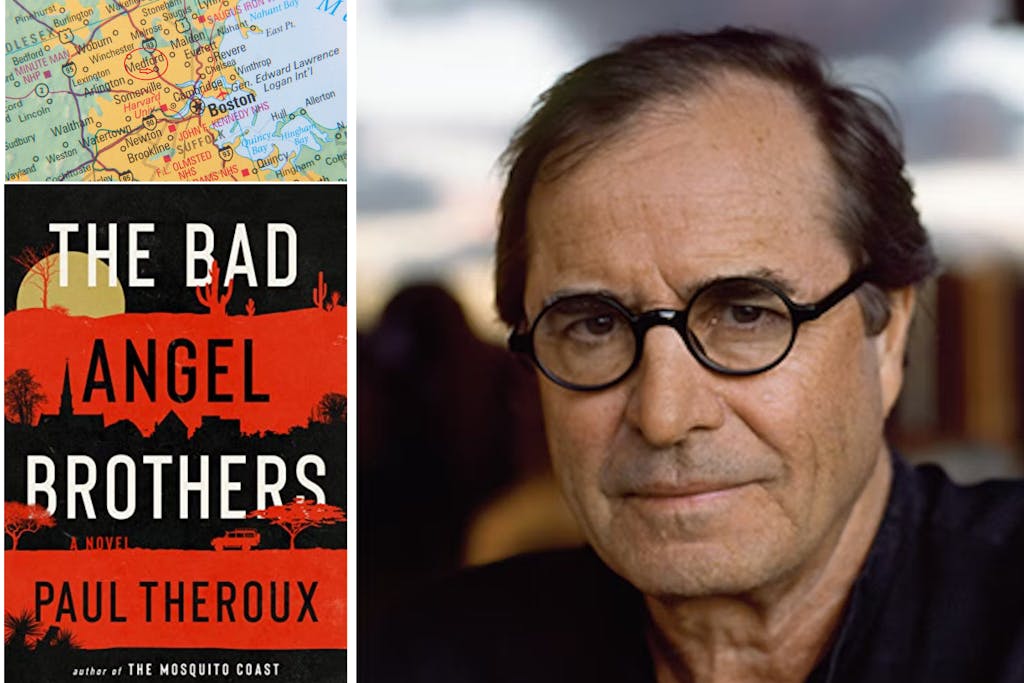

Paul Theroux’s New Novel Offers a Helping of New England with a Touch of Terror

We know Paul Theroux as a brilliant writer, of novels, travel tales, screenplays and crime novels, among other works. You may also know him as a loyal Silversea traveler whose enticing travel writing delights and entertains readers of Silversea’s Discover blog. But now, we’d like to introduce a slight plot twist: He is the author a new psychological thriller that puts brothers at the heart of the conflict.

“The Bad Angel Brothers,” out in September, is the disquieting tale of Cal and his brother, Frank, born and raised in the New England town of Littleford, Mass. Littleford, as Theroux draws it, is every bit as picturesque as a clichéd Christmas card drawing in which the snow-laden boughs provide the backdrop for one candle whose flame burns brightly.

As do the passions in this novel. But this isn’t about lust. Instead. It’s about, as The New York Times called it in its review, “fratricidal ire.” Frank and Cal’s relationship is so fractured they make Cain and Abel look like poster boys for brotherhood.

We caught up with Theroux to ask him how his own New England upbringing influenced his novel and whence came the startling details about precious metals and gemstones.

Silversea: How did you draw the character of Littleford?

Paul Theroux: I grew up in Medford, Mass., and Littleford is based on that town, a suburb of Boston [about six miles away], neither city nor country, but with a lovely river running through the middle of town, the Mystic River, which often seemed mystical to me.

SS: What are some of the quirks of the place or places you lived in New England or on Cape Cod that you incorporated into the story?

PT: Certain words and speech patterns are characteristic to this area. The “Boston accent” doesn’t exist – I mean, there are 10 different Boston accents, but there’s a shared Boston vocabulary: saying “tonic” for “soda,” or “bollocky” for “naked,” and many others. I tried to use them all.

SS: Is there a real-life version of the Littleford Diner, where Cal and Frank often meet for some tortured meals, or was it a composite?

PT: I think all medium-sized towns in New England (and maybe the U.S.) have a diner – not just a restaurant but a meeting place, which is a sort of club.

SS: The opening lunch that Frank and Cal have (and subsequent ones) are very New England-y. How would you describe New England cuisine, beyond clam chowder?

PT: I think the key to New England cuisine is local ingredients that are not messed with – steamed clams, boiled lobster, grilled haddock, pot roast, new potatoes, sweet corn and seafood chowder (a big step up from clam chowder) and so forth. But there are ethnic groups with deep roots – Italian, Irish, French Canadian – and their dishes are everywhere, along with Chinese, Vietnamese and others.

SS: What does cuisine say about the character of a place? You’ve traveled the world and certainly know more about what that means to a traveler.

PT: What I’ve found is that in many places the main aspects of culture are language and food – that people don’t have material possessions, but they do have these two important features of their identity. So, speaking their language and sharing meals is the best way to get to know such people and to make friends.

SS: The interactions that Cal has with his mother strike me as loving but with a touch of formality. I contend that Easterners do tend to be more formal; agree with that or disagree?

PT: It’s possible that Easterners are formal, but I have traveled a lot in the American South and wrote a book about it (“Deep South: Four Seasons on Back Roads”) and I found that, although there is a superficial warmth in the South – the greeting – it is more a way of sounding out a stranger. People in New England rarely greet strangers, and if you say hello, the stranger might take you to be drunk or crazy. Families are another matter – complex wherever you go.

SS: What do you want the reader to come away thinking about Littleford? I was uncertain whether the character Cal loved it with a touch of loathing or whether he really disliked it because Frank had poisoned the well, so to speak.

PT: The small town is like a family, with all the pluses and minuses, but most of all the members of the community know you and your history and such knowledge can make you vulnerable.

SS: Who had more New England in his bones, Cal or Frank? I found it interesting that the ever-ambitious Frank never left. Does that stand to reason because he wasn’t really a risk taker and only played the hand when he had four aces?

PT: The big contrast in the book is between the brother who stayed [Frank] and the one who left: Cal, the traveler, has been enriched by his travels and has a sense of self that the stay-at-home doesn’t have

SS: Geology played a large role in this novel–lots of incredible detail. [Cal is a geologist who travels the globe in search of all kinds of treasure – gold, gemstones, cobalt.] Where did that come from?

PT: I needed Cal to have a real and believable occupation, and, of course, geology can take you around the world. I have a good friend who spent his early working life looking for gold in the American Southwest, and I had long talks with him and other miners and geologists, and, of course, I read lots of books.

SS: Having just been in Colombia, I was fascinated by the emerald mines and began to think of people who may purchase gemstones in their travels. Do you have advice for purchasing gemstones in travels?

PT: I really have no advice to give about buying gemstones. I have bought rubies in Burma and Thailand, and amethysts in Zambia, and tanzanites in South Africa. I bought them because they looked pretty – yes, I was probably overcharged, but they still look pretty.

SS: What did you do to prepare for writing this? What inspires you to try other genres, reinventing them as you do?

Romulus and Remus, and all the feuding brothers in a particular circle of Dante’s “Inferno.” Because I come from a large family, I am fascinated by the dynamics of big families, or siblings, and I wanted to dramatize the sort of tensions that result in fratricidal feelings. How do such feelings start? How do they build – and are they acted upon? A novel is the best way of giving life to such feelings, and so I found it very satisfying to write.

SS: Do you regard travel as a mission?

PT: As a child – and probably like most children – I dreamed of going to distant places and imagined myself an explorer. I read books of travel and reading helped color my fantasies. I longed to leave home, and when I graduated from college – a week later – I flew to Italy and got a job (I had studied Italian in high school), and from Italy became a Peace Corps teacher in Central Africa. I have been on the move ever since, not as a mission but to look closely at the world and to wonder where the world has been, what’s it like now and where it is headed.