In Vancouver, Artist Bill Reid Led the Resurgence of First Nations Art. You Shouldn’t Miss It.

It’s the world’s greatest sculpture, nestled in the most spectacular metropolitan landscape.

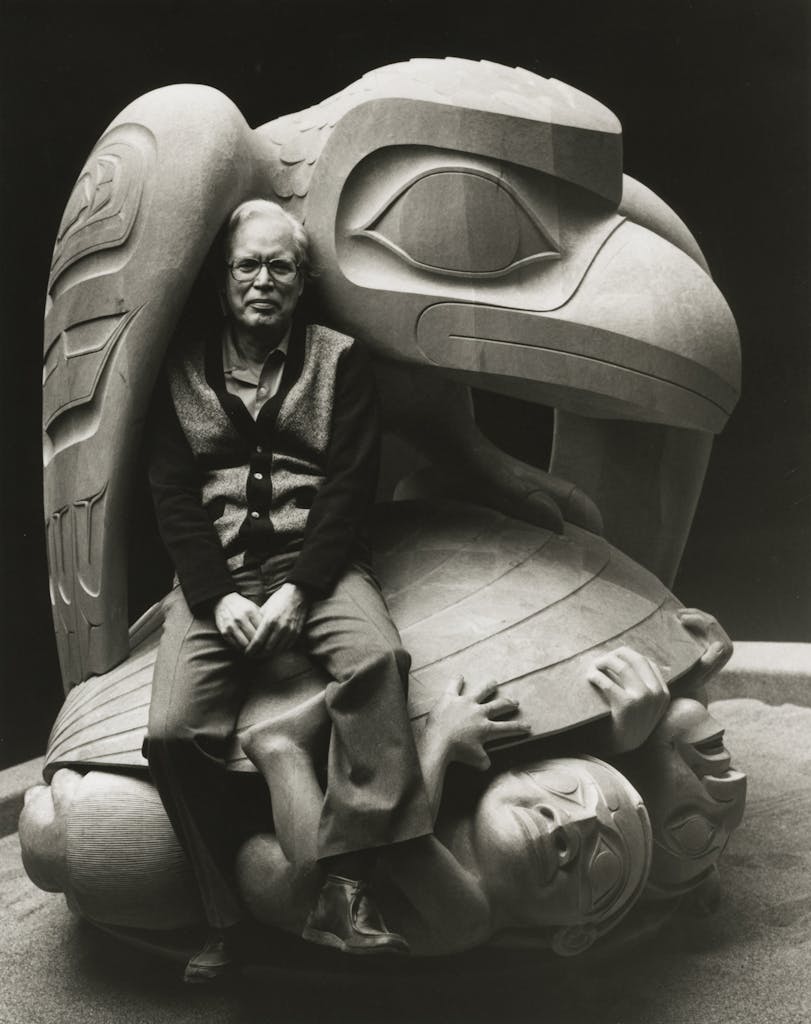

Vancouver is justly famed for many things — an unparalleled setting among azure North Pacific inlets, backed by ivory snowcapped mountains among them — and those things include the work of legendary First Nations artist and carver Bill Reid. The most magnificent of all is “The Raven and the First Men,” an unforgettable carving that depicts the origin story of northern British Columbia’s Haida people.

This massive piece of laminated yellow cedar, set in its own alcove at the UBC Museum of Anthropology, is a burnished amber beacon of artistry and meaning. It depicts the ancient Haida oral story about Raven encountering a large clamshell on a beach in Haida Gwaii, in the Haida homeland along the North Pacific Rim. Intrigued by a commotion emanating from inside, Raven opens the shell and finds a group of humans clamoring to get out.

In most North Pacific indigenous cultures, Raven is the “trickster,” a querulous, ever-busy instigator of change and turmoil. In this case, he opened the shell not just out of curiosity but as part of his innate role as a catalyst. Several timid proto-humans peered out, then clambered from shell to beach. And so began the history of the Haida people. Reid’s interpretation of this origin story is a mesmerizing work of art whose power and beauty surpass every sculpture I’ve ever seen.

My superlative declarations about The Raven are subjective, of course—I’m an unabashed fan of Reid’s work, and I make no apologies. Yes, I’ve seen Michelangelo’s Pieta, and it too is magnificent. I’ve viewed countless works by Calder, Brancusi, Giacometti, Moore, Bourgeois, Rodin and more. And I’ve seen the work of hundreds of North Pacific indigenous carvers, historic and modern, all wonderful. The Raven stands out for its deep human meaning, a facet equaled only by the Pieta.

It is memorably imposing. Its 4.5 tons are composed of 106 yellow cedar beams that were kiln-dried for almost a year, then laminated into a single block of wood, more than 6 feet square, by a Vancouver company with deep expertise in the craft. Its golden wood glows, aided by a skylight above that draws in the high, clear light of the North Pacific. Its display alcove allows you to walk entirely around it, simultaneously admiring its grace and absorbing its power.

It took Reid and four helpers two years to shape and polish it in a carving shed on the museum’s campus; meanwhile, famed Canadian architect Arthur Erickson, designer of the museum and many other standout buildings, created the special alcove for Reid’s piece. Once it was finished, a crane lowered it through the skylight opening, and it was unveiled and dedicated April 1, 1980, by the Prince of Wales (now King Charles III).

“The Raven” achieved instant fame, still holds pride of place at the anthropology museum and is arguably the premier art attraction on Canada’s West Coast, if not the entire country. The Canadian government honored that significance by placing it on a $20 bill in 1990.

It is thus the pinnacle of Reid’s career, but it represents much more than that. It’s also the pinnacle of the 20th century revival of indigenous art and culture. Reid would have shunned any such title, but he was its catalyst and leader.

“Artist, poet, writer, intellectual, broadcaster, activist — Bill Reid was a huge, pivotal force in Canadian culture,” says Karen Duffek, head of the Curatorial + Design Department at MoA.

At the beginning

Reid, born in Victoria in 1920, was of Scottish-German and Haida heritage. He was working as a radio announcer and studying goldsmithing in midcentury Toronto before returning to British Columbia to take up the nearly dead mantle of Haida art, to which he had been exposed by his grandfather, Charles Gladstone. The latter was the nephew and heir of Charles Edenshaw, a famous 19th century Haida carver, but the art practiced by Edenshaw and compatriots had fallen into decline during the early 20th-century Canadian campaign to eradicate indigenous culture.

Reid’s initial success with jewelry and modest-sized carvings — “The Raven” is based on a much smaller 1970 boxwood piece you can hold in your hand — brought coastal indigenous art new renown, enticing gallery owners, museum curators and many nascent First Nations artists to take up Reid’s mantle and adapt and expand this unique art form for modern eyes.

How Bill Reid revitalized indigenous culture in Canada

This, in turn, helped revitalize indigenous culture. Nearly extinct languages found new students. Band councils that had been quiescent for a century awakened to raise their voices on regional issues such as deforestation. Potlatches — once banned under Canadian law — regained their historic importance in First Nations communities. Indigenous cultural threads made their way into fashion, music, literature, cuisine and more. Finally, capping Reid’s fame, the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art opened in downtown Vancouver in 2008, providing a sparkling dedicated space for works by Reid (including a medium-size onyx version of “The Raven and the First Men”) and many other First Nations artists.

“It’s safe to say that the impact he had will be felt for generations to come,” says Aliyah Boubard, Bill Reid Gallery assistant curator. “He really bridged the relationship between the traditional art of the Northwest Coast and the contemporary art we are now seeing.”

From the vantage of the 21st century, it can be difficult to grasp how amazing the First Nations cultural resurrection is. The Haida, like so many other indigenous groups, were nearly wiped out not by war but by disease — 99 percent mortality from smallpox, measles and more in Haida Gwaii, for instance. The islands that had once held 20,000 people had, near the end of the 19th century, barely 600 indigenous inhabitants.

Succeeding generations were then subjected to deliberate campaigns to erase their culture. Authorities seized potlatch regalia, such as masks and robes, and sold them to collectors. The now-infamous 20th century boarding schools for Native children forbade all expressions of cultural heritage — language, music, art. On my first trip years ago to Haida Gwaii, I met an artist my age who had been sent to a boarding school in Victoria and whose hands were beaten if he drew anything. Yes, anything.

Framed against this backstory, Reid’s achievements seem spiritually boundless.

My superlative declarations about “The Raven” are subjective, of course — I’m an unabashed fan of Reid’s work, and I make no apologies. Yes, I’ve seen Michelangelo’s “Pieta,” and it, too, is magnificent. I’ve viewed countless works by Alexander Calder, Constantin Brancusi, Alberto Giacometti, Henry Moore, Louise Bourgeois, Auguste Rodin and more. And I’ve seen the work of hundreds of North Pacific indigenous carvers, historic and modern, all wonderful. “The Raven” stands out for its deep human meaning, a facet equaled only by the “Pieta.”

For one thing, it is far more complex than the simple visual story it offers at first glance. Look more closely, and a couple of Reid’s first humans are ducking back into the shell, having scanned life outside and, well, looks dangerous, maybe later, OK? Another close look reveals that each of the half-dozen little people has a different personality — an embellishment of the origin story that Reid added because, well, the spirit moved him to do so, and although his work is rooted in Haida tradition, it is not bound by it.

“People are actually doing something, moving around, which is really very much of a European concept of sculpture,” Reid explained later. “I guess there are lots of paradoxes which I’ll leave for other people to unscramble.

“It’s a version of ‘The Raven’ myth for today, not for the time when it was created.”

Here’s why you must visit Vancouver’s Museum of Anthropology

The Museum of Anthropology, the facility that is its home, often is considered best of its kind in the world. It’s devoted exclusively to the arts and culture of North Pacific peoples, and that is a rich and varied tapestry. British Columbia alone holds three dozen distinct First Nations groups; the museum itself is on the lands of the Salish Musqueam people and acknowledges this with a welcome figure created by Susan Point, one of the leading Salish artists of modern times.

Also in the museum is a lavish display of Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonial masks. These memorably vivid works depict many of the spirit beings that, like Reid’s Raven, hold great importance in indigenous tradition and culture and are largely meant for ceremonial use. Canadian authorities in the early 20th century seized many such masks, and they appear here with the cooperation of the clans whence they came. Others represent the work of contemporary crafters who, like Reid, have adapted traditional designs to modern artistry.

Other Reid works hold prominent positions around Vancouver. His “Killer Whale” greets visitors to the Vancouver Aquarium in Stanley Park. “The Jade Canoe” is an immense bronze depiction of Earth’s creatures, navigating life’s seas in the same boat. Appropriately, it welcomes travelers in the International Arrivals terminal of Vancouver International Airport, and is populated with another set of Reid’s unique little creatures.

Occasionally one can see works by Reid for sale in galleries around the city: prints, small pieces of jewelry and such. They are beyond expensive but provide for great moments of wistful covetousness.

Perfect day in Vancouver

A superb day in Vancouver would start with a morning visit to the MoA, followed by lunch at Granville Island’s lusciously populated public market, and an afternoon browsing the many galleries and stores. Eagle Spirit Gallery, for one, is the largest aboriginal art gallery in Vancouver, and among the foremost purveyors of indigenous art in North America.

All these works of art, from silver bracelets to towering totems to massive sculptures, are alluring, but they also represent the strength and grace of a distinctive ancient art form. Its revival represents the modern renaissance of a branch of humankind that, almost driven to extinction, is alive and thriving. Perhaps more than anyone else, Bill Reid helped make that so, opening a new clamshell on a new beach-head. I hope all visitors to British Columbia will consider Reid’s comment about his “little creatures” in the clamshell:

“I see them as unformed,” he said, “having all the potential of being human but having no way of achieving that until they emerged from the clamshell.”