Relax. Here’s How to Behave in an Onsen, a Japanese Bath

I first encountered Japan in my youth, when I moved to Tokyo to teach on a two-year fellowship. Those two years changed my life. I fell in love, first with the culture and then with a Japanese woman, and Japan has been an interwoven part of my life ever since.

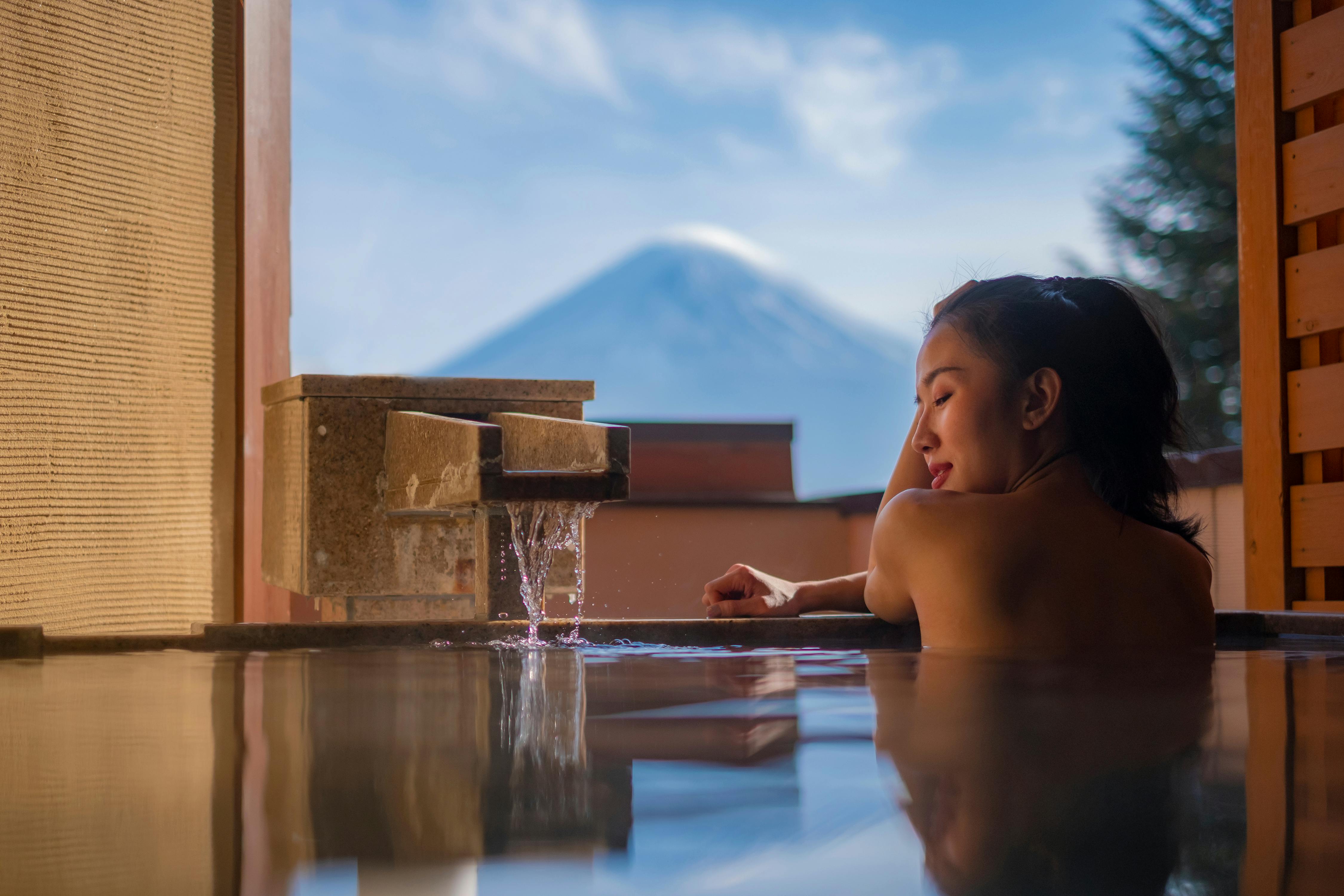

In the ensuing years, a blissful soak in a hot spring bath, or onsen, has become a cherished Japanese ritual for me. It is relaxing, and it also is one of the oldest threads in the tapestry of Japanese culture. When you immerse yourself in an onsen, you become part of the exquisite weave of Japanese life.

The experience will provide special insights into Japanese culture, but you need to know some background and, perhaps more important, the proper etiquette to enjoy your visit and a couple of stumbling blocks that may await you. Here’s what you need to know to get the most out of your onsen visit.

An ancient tradition in modern times

The original meaning of onsen is “hot spring.” Because Japan is a volcanic country on the Pacific Ring of Fire, hot springs are ubiquitous on all the islands. From earliest times, onsen have been associated with purification and healing, based on the pools’ salubrious mineral contents.

The Nihon Shoki, written in 720 and one of Japan’s oldest works of literature, mentions three onsen: Shirahama Onsen and Arima Onsen, both in the central part of Honshu, Japan’s main island; and Dogo Onsen, on Shikoku island. Ancient texts record that these onsen were used for rituals of purification in the native Shinto religion and that the emperors visited them.

A second meaning of onsen is a bathing facility built around a hot spring. Today, you will find about 3,000 such facilities in Japan. For many Japanese, a trip to an onsen – whether a large public hot spring bath in the middle of a city or an outdoor rotenburo bath in a secluded forest – is a regular ritual.

How to behave in a Japanese bath

On your visit to Japan, you will have the opportunity to enjoy an onsen experience for yourself. Doing so provides special insights into Japanese culture, but you’ll also need to know how to navigate.

When you enter the bathhouse, an attendant will greet you, ask you to remove your shoes and offer you slippers. Then you will be directed to the men’s or women’s changing room.

In the olden days, men and women used the same onsen, but after Westerners became more ubiquitous in Japan in the 19th century, onsen were divided into male and female baths. You can still find traditional mixed-gender baths in the deep country, but the onsen you visit probably will have one section for women bathers and one for men. You will know which is which by the banners that are usually hung at the entrance to these rooms – pink for women, blue for men.

Note: If you have tattoos, it is best to cover them with an adhesive bandage before you visit. That’s because in Japan, tattoos often are associated with organized crime. That attitude is changing slowly, but many onsen still do not allow bathers with visible tattoos. In some cases, you may be offered a private bath, if available, if the tattoo cannot be covered.

Once you enter the changing room, you will find a clean space with lockers or baskets in which to place your belongings. Take off all your clothes and place them in a locker or a basket. Phones and cameras should also be left in your locker. Some lockers will offer a key on a flexible band you can wrap around your wrist.

Visitors sometimes ask whether swimsuits are allowed in the onsen. The answer is no. Everyone bathes naked. It is normal to feel hesitant about appearing naked in front of strangers, but keep in mind that the Japanese do this every day. For them, there is no embarrassment in communal nudity in the onsen; in fact, from childhood, they are taught that this is natural and to be expected. Leave your modesty in your locker with your clothes, and enjoy this opportunity to immerse yourself in Japanese tradition.

After you have stored your belongings, you will see shelves holding two kinds of towels, a 6-inch-square washcloth and a larger bath towel. For now, help yourself to a washcloth. Then slide open the sliding door that leads to the onsen pool room.

Inside, you will see a steamy room with multiple pools. You will also see showers, knee-high taps, plastic or wooden stools, and plastic or wooden buckets.

Important: Do not enter pools yet.

In the Japanese way of bathing, you first soap and rinse your body thoroughly outside the bathing pool. This is fundamentally to keep the water clean, but it also serves to warm your body so it may more quickly adjust to the temperature of the bath.

Find a free shower or spigot. Soap and shampoo will be provided. If you are using the spigot, fill the bucket with water and pour it all over yourself, then soap yourself thoroughly. Do this as many times as needed. Then use the bucket again to thoroughly rinse yourself off. Make sure you do not inadvertently bring any soap suds into the pool.

After you have rinsed yourself thoroughly, you will usually have a selection of pools to choose from, all set to different temperatures. Dip your hand in to find the temperature that suits you best. Most Japanese like it hot.

Slowly sink into the muscle-soothing, soul-caressing waters. The goal of immersion in the onsen is to relax completely. If you have come with friends, you can chat quietly with them. As a visitor, I always find it delightful to watch Japanese, who interact with one another in the baths with a steamy congeniality. There is even an expression for this: hadaka no tsukiai, or naked camaraderie, sometimes also called skinship.

How long should my soak last?

You can stay as long as you feel comfortable. For most people, 10 to 15 minutes will suffice, but some luxuriate longer. However long you stay, do as the Japanese do and surrender yourself to the steaming waters, letting your aches and cares slide away.

After the onsen, you may wash yourself again in the shower/tap area, but because the onsen waters are thought to have curative mineral properties, most bathers prefer not to rinse afterwards. Return to the locker room, take a large bath towel from the shelf, dry yourself off, and dress.

Then re-enter the world, feeling a little closer to the heart – and the heavenly heat – of Japan.