Soak up History and Majestic Views on This Step-by-Step Tour of London’s Bridges

Bridges are to London what skyscrapers are to Manhattan. Outside of their practical role as spans over the Thames, some have risen to landmark status in their own right.

Each has a distinct history, aesthetic design and, perhaps most important for return visitors, fresh vantage points on the cityscape. To see London from its bridges is to fall in love with the city again and again, no matter how well you think you know it.

Visitors often mistake the castle-like landmark near Tower Hill for the more mundane London Bridge (the one always “falling down” in the nursery rhyme), even though they look nothing alike,

An easy 10-minute walk separates the two. The jaunt left me wanting more. Surely there were more bridges and views? I quickly mapped a longer route along the river, adding more spans (Southwark and Millennium) and time to explore anything interesting in between. I was well-rewarded. My time-traveling ramble covered about two miles each way — and centuries of the city’s history.

Bridges back in time

Bridges in London got their start in ancient times. The Romans, who founded the city in the 1st century CE, built successive wooden bridges at the site of London Bridge. The city’s oldest crossing remained its sole crossing — often jammed, taking hours to traverse — until the mid-18th century.

As the city grew, so did the number of bridges. Today, more than 30 bridges cross the Thames, many replacing older ones that didn’t last — except in the imagination.

French Impressionist artist Claude Monet spent three years capturing the way natural light played on the old Waterloo Bridge (not the one that stands today). The long-ago-replaced bridge lives on in the 41 paintings he created between 1900 and 1904 that now hang in museums around the world.

Tower Bridge

Standing on the deck of Tower Bridge(photo at top), I felt puny beneath the neo-Gothic towers that soared more than 200 feet skyward. Silversea Cruises to Lisbon, Helsinki and other destinations start at the bridge, making this a worthy pre- or post-cruise walk.

The bridge isn’t as old as it looks. It opened in 1894 but was designed to look much older to blend in with the nearby 11th-century Tower of London. Views sweep from old to new, from the Tower, St. Paul’s Cathedral and the sleek glass skyscraper the Shard in the west to Canary Wharf in the east.

The bridge has a sidewalk for pedestrians and roads for vehicles, which occasionally open to let tall ships through. It’s a bascule bridge (bascule is French for “seesaw”), or drawbridge, meaning the decks rise and snap back into place.

For more daring views, there’s an upper walkway — 137 feet above the river — that has a transparent floor that stretches 200 feet between the two towers. Eurostar’s website may have captured it best, describing it as “a nerve-testing glass walkway” from which you can see double-decker buses and boats whiz by below.

I lingered on the bridge to take in its splendor. Hard to believe it was once chocolate brown, especially because of its current red, white and blue palette, dating to 1977 when it was painted in honor of Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee.

London Bridge

I crossed the bridge and followed the south banks of the Thames, literally walking out of the 1.12-square-mile city of London. (Everything else is a borough.) I passed what was once City Hall, a sloping glass orb resting on its side. Others have called it a helmet, misshapen egg and (thanks to former mayors), part of the male anatomy. It’s 10 stories tall but closed to the public.

When I arrived at London Bridge, I did a quick out-and-back to catch the views. The low-slung bridge completed in 1972 lacks ornamentation, but the views still wow. The oddly leaning Sky Garden building and the skyscraper aptly nicknamed the Gherkin felt close enough to touch from this vantage point.

I couldn’t help thinking about past bridges that once occupied the spot where I now stood. The “falling-down” bridge, I later learned, referred to a stone arch bridge started in the 12th century that lasted more than 600 years before falling into disrepair (hence the rhyme).

The replacement bridge stood for more than a century before it was sold to an American businessman. It was dismantled — all 10,276 granite blocks — and reassembled over the Colorado River in Lake Havasu, Ariz., where tourists come to splash beneath its arches.

From the bridge, I dipped into the neighborhood along Borough High Street to Southwark Cathedral, the site of one of the oldest churches in the city of London.

I was touched by a sculpted granite memorial to a Mohegan chief from the Connecticut colony. Mahomet Weyonomon traveled to England in the early 18th century in hopes of enlisting King George II’s help in protecting his land from renegade white settlers. While waiting to meet the king and propose a pact, Weyonomon, 36, contracted smallpox and died.

As a foreigner, the chief could not be buried in the city of London so his body was taken just outside city limits and buried there. In 2006, modern-day tribal members traveled to the site to hold a proper burial ceremony and unveil the striking memorial made of pink granite from the chief’s native Connecticut.

I continued along the river’s banks to the one-time impoverished area around St. Saviour’s Dock, which Charles Dickens used as a backdrop in “Oliver Twist.” Today a gleaming granite sculpture called “Exotic Fruit” stands as a symbol of the cargo that once came to this dock from all over the world.

Farther on, I passed the Clink Prison Museum, a 12th-century torture chamber (in case the Tower of London wasn’t horrific enough) that’s part-cheesy and part-educational. Most of the original building is gone, but the stories of what was done to prisoners and the instruments of terror create a haunting reminder of human misery.

Southwark Bridge

A half-block or so, I came to the century-old steel-arch Southwark Bridge. It’s quieter than the other bridges and a good place for views of the Shard and the Walkie-Talkie Building, so named because its bulging profile resembles a two-way radio handset. I looked back on Tower and London bridges too.

After seeing the vistas from the middle of the bridge, I returned to the south bank and passed by The Globe, a modern-day re-creation of the theater where William Shakespeare debuted many of his famous plays.

Millennium Bridge

Soon, I came to the low-profile Millennium Bridge, officially named the London Millennium Footbridge. The suspension bridge for pedestrians has a beautiful winged web design that made me feel as though I were walking on air. It got the nickname Wobbly Bridge after it opened in 2000 and people complained that it swayed. Repairs took two years, but the bridge has since become a city landmark.

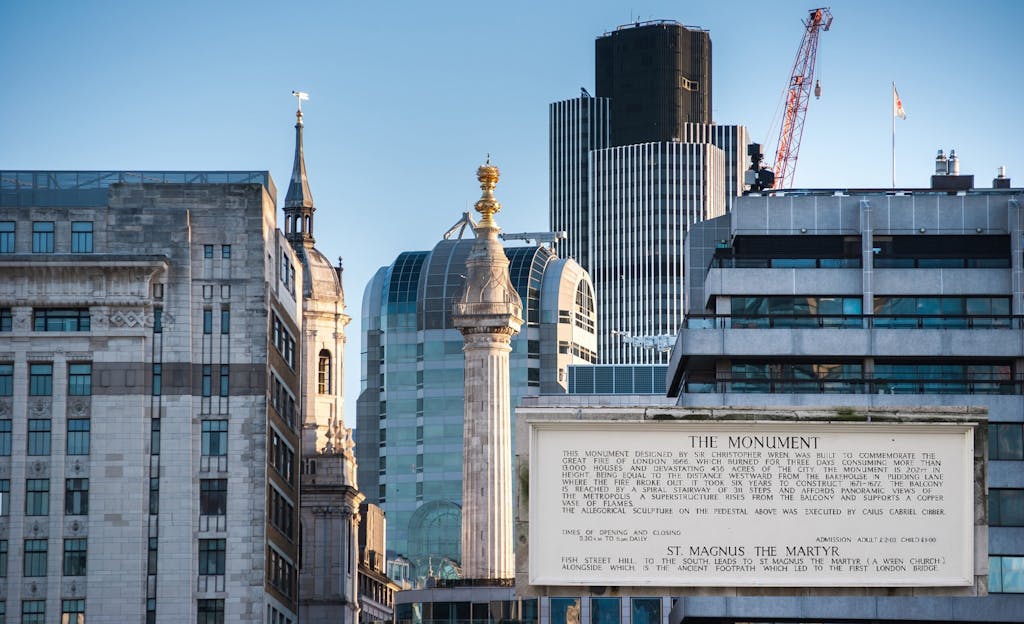

From the south bank, I could see the former powerhouse that’s now the Tate Modern and looked straight across at St. Paul’s Cathedral. I retraced my steps to head back toward Tower Bridge and this time crossed London Bridge. I stopped to visit the Monument to the Great Fire of London (known mostly as “Monument”) designed by Christopher Wren. The 17th century tower is a memorial to the massive destruction from the fire of 1666. It’s 327 steps to the viewing platform on top to take in more panoramas of the river and the city.

From here, I relied on a series of walkways to guide me back to Tower Bridge and thought about all the other bridges in London I had yet to walk.