The First-Timer’s Guide to South Korea’s Seoul

The Korean alphabet is shorter than the English one by two characters, but the work week tends to be longer. When it comes to technology, robotics are all the rage, and Korean music and movies have muscled their way into the mainstream. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect on my first visit to Seoul, but here’s what I wasn’t expecting: Seoul soothed me.

In five winter days as a rookie among Seoul’s palaces, parks and marketplaces, I gained 4 pounds despite walking countless miles down alleys full of people but empty of graffiti and litter.

For two of those days, I relied on translator/guides for help. Otherwise I trusted Seoul’s multilingualism, which includes subway signs and museum labels in Korean, English, Japanese and Chinese. That worked fine.

In fact, for anyone accustomed to U.S. metro areas, the hospitality, cosmopolitanism, technological acumen, influential popular culture and relentless tidiness of South Korea’s capital (population about 26 million) are likely to feel inviting, humbling and tranquilizing.

Here are a few things a first-timer learns in Seoul:

One of the astonishing things about Seoul is that nearly all of it has been built in the last 65 years. South Korea since 1953 has gone from scorched earth to one of the world’s strongest economies, cranking out Samsung and LG phones and Hyundai and Kia cars, along with pop music and TV dramas that entertain millions of people beyond its boundaries.

But the city does have five restored palaces, all traceable to the Joseon Dynasty that ruled Korea from the 1390s to the 1890s.

In those five centuries, the Joseon kings, their civil servants and soldiers created a writing system, spread Confucian philosophy and built a culture that endured a seven-year Japanese invasion in the 1590s; a Japanese occupation from 1910 to 1945; and the Korean War of 1950-53, which killed at least 2.5 million people (by Encyclopedia Britannica’s estimate) and separated Russian-backed North Korea (officially the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) from U.S.-backed South Korea (officially the Republic of Korea).

It makes sense to start with a tour of the reconstructed Gyeongbokgung Palace, where the first Joseon king presided. There are stately tiled roofs. Elaborately painted ceilings. Expansive grounds. And if you can be here at 10 a.m. or 2 p.m., you’ll see a ceremonial changing of the guard at the palace’s Gwanghwamun Gate.

Fascination of facial hair

You’ll know the 20-minute ceremony is starting when you hear the slow beat of a booming bass drum and see sumunjang (guardsmen) in bright colors bearing flags through the Gyeongbokgung courtyard. Notice the scimitars, the spears and the fake mustaches — a clue that these are re-enactors, not soldiers.

The changing of the guard is a tourism-driven tradition because there is no Korean royal family left to protect. Enjoy it and grab a selfie or two with an unsmiling guardsman. But also remember that South Korea has a very real, very busy military at work along the Demilitarized Zone 35 miles north and beyond.

Designs on a palace

If it’s Tuesday, Gyeongbokgung Palace is closed. In that case — or if you’re keenly interested in design —head for Changdeokgung Palace.

This palace (closed Mondays) is bigger than Gyeongbokgung, and many of its buildings date to the 17th century.

But don’t imagine that this palace has always been placid and happy. If you sign on for a tour of the palace or gardens, ask the guide how Jeongjo of Joseon came to the throne in the 1770s and brace yourself for a tale of palace intrigue and filicide as horrifying as any gothic drama.

Did someone say shopping?

Myeong-dong is one of the city’s foremost shopping districts, packed with hotels, restaurants, food stalls and visitor favorites such as the Nanta Theater, which offers a wordless, kid-friendly musical comedy about a kitchen crew preparing a wedding feast.

A network of narrow alleys between the skyscrapers compresses people, bright lights and food smells in a dramatic way. In the restaurants, you’ll find kimchi (salted and fermented vegetables), gochujang (fermented bean paste), bulgogi (marinated beef and pork) and bibimbap (rice dishes). Out among the stalls, you’ll glimpse corn, sausage, seafood, fruit, churros, lobster, chocolate and more, sometimes in startling combinations.

The people-watching is top notch too.

To markets, to markets

Myeong-dong and other Seoul districts have plenty of intriguing alleys. But Gwangjang is renowned for having the most food stalls, about 200, many offering mung bean pancakes, the market’s signature dish. Two people can dine on a sampler plate stacked with bean, fish and beef cakes for about $10. Take a seat, watch the world squeeze by and, if you can find a common language, shoot the breeze with your cook.

For a change of pace, take a stroll along the market-adjacent Cheonggyecheon Stream, a park (with walkways and burbling waters) that offers a measure of calm in the middle of the city, covering several miles and passing beneath about two dozen bridges.

A whisper campaign?

Glimpses of Seoul as it stood before 1953 are rare, so it’s a good idea to visit Bukchon Hanok Folk Village, a neighborhood of homes from centuries past, ingeniously restored and still occupied. Residents post signs in four languages to discourage tourists from trespassing and urge them to whisper. Which, remarkably, they do. The main street leads to a hilltop with splendid views of the old tile roofs in the foreground, the modern skyline beyond.

It’s time to dress up

When you approach a palace or historic neighborhood, you can count on seeing fellow tourists in hanbok — historical costumes designed to mimic fashions of the Joseon Dynasty. These are especially popular among selfie-snapping young women and families from Asia, but all nationalities are welcome at the hanbok shops that rent costumes by the hour or day; $15-$20 for four hours is typical.

As an American who doesn’t have Korean roots or take a lot of selfies, I wasn’t ready to suit up. But you (or your teenager) might like to. If so, you get free admission to the palaces.

On top of the world

Namsan Seoul Tower, completed in 1969, rises 777 feet above 800-foot-high Namsan Mountain. The result is an unbounded view of skyscrapers (nearly all built since 1969), the surrounding hills and valleys of the city, the Han River and the wealthy, modern commercial district of Gangnam (which means “south of the river” in Korean).

The Namsan Cable Car can take you to the top of Namsan Mountain for about $9 round trip. There’s plenty to see and snack on, but for the biggest views, pay $10 more for the elevator ride to the tower’s wraparound observation deck.

Indelible memories

Many sources warned me about the touristy and expat-centric nature of the Itaewon area, so I left it off my itinerary. Despite similar warnings, I kept on the Insa-dong area because its legions of souvenir shops are neighbored by many art galleries and the Buddhist Jogyesa Temple.

If your kitsch threshold is low, you might want to advance straight to Samcheong-dong. I landed in this trendy neighborhood because I wanted to try the widely praised barbecue at the Maple Tree House restaurant. But as my guide circled the neighborhood in search of a parking space (a common and difficult activity in Seoul), I found myself wishing I had another hour to knock around Samcheong-dong’s dozens of shops, galleries and cafes, as many young, trendy Seoul locals were doing.

Up and down

The Noryangjin Fisheries Wholesale Market, easily reached by subway, is mostly within in a slick building that opened in 2016. You step inside, confront a dizzying array of sea creatures, challenge yourself to eat adventurously, then make purchases. If you like, vendors will immediately send those purchases upstairs to be cooked per your request.

It isn’t cheap, but you will remember the day. My guide and I spent about $130 browsing and consuming a massive late lunch of crab (steamed), abalone (roasted) and octopus tentacles (raw), still coiling and uncoiling though no longer attached to their original owner.

Some people claim to love them, and I felt obliged to try them. I didn’t get the appeal beyond the novelty of eating something that’s still moving. They’re very chewy and not nearly as satisfying as abalone and crab. (For the record: They’re not alive despite the twitching. The posthumous coiling has to do with how their nervous systems are wired.)

If you’re a photographer, you’ll also want to step into the old fish market building, which dates to 1971 and, during my visit, still had more than a dozen merchants. It’s a smellier, moodier, darker, more cinematic place, well-suited to a Jason Bourne chase scene.

A medley of neighborhoods

For a good walk, start at the Seoul City Wall Museum in the Dongdaemun District. From there, follow the path along the wall, which dates to 1396. The route will take you through blue-collar neighborhoods of old low-rise houses, with increasingly grand views. You’ll eventually reach Naksan Park, at the top of Naksan mountain, where several footpaths converge and there are courts for badminton and foot volleyball.

You’ll also see the boldly colored walls of the Ihwa-dong Mural Village, which includes the Noh Bak Gallery, Lock Museum, sculptures suspended in mid-air and an immaculately decorated cafe that specializes in coffee, sausages and beer.

The belly of a beast

Dongdaemun Design Plaza, a sinuous metal-and-concrete beast of a building by architect Zaha Hadid, takes up a big chunk of the low ground in the Dongdaemun District. Hadid’s blank walls were a bit much for me — why not let artists use a few square feet of those big, empty spaces? — but it’s visually fascinating. On one side is a design museum and on the other a collection of design-oriented shops.

The true character of Seoul

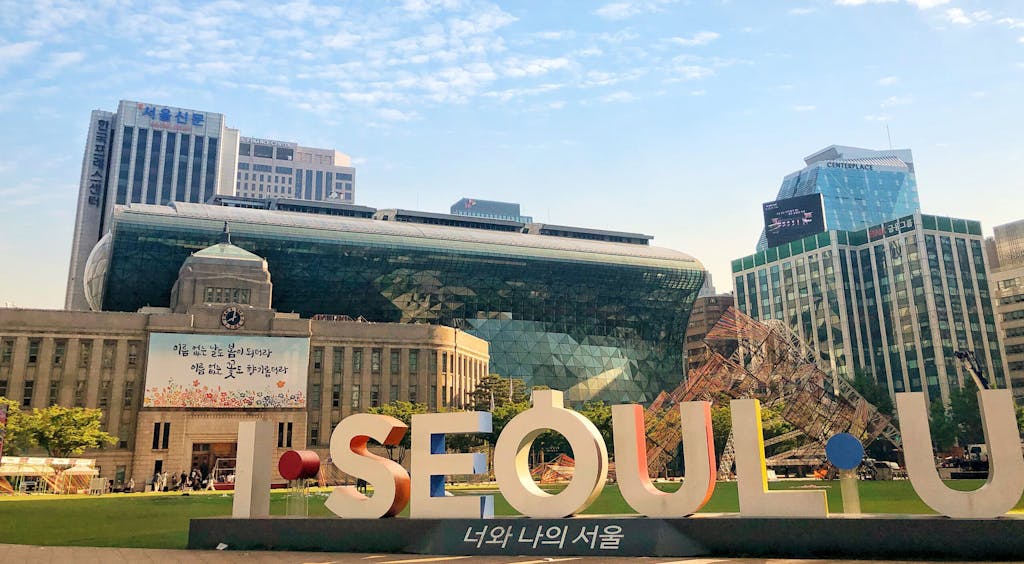

I wanted to take in a few more architectural landmarks so I strolled past Seoul’s gleaming blue-glass City Hall (completed in 2013), which rises above the old stone Art Deco City Hall (completed in 1926 and now a library).

These two cool buildings are neighbored by a public plaza where political demonstrators often gather. The only off-note of my stop occurred as I walked past an anti-North Korea demonstration, when one young man faced me and suggested I leave.

I ignored him but caught a subway to the Old Seoul Station, the site of another 1920s building neighbored by a modern addition. Here, too, demonstrators crowded the area — but this group was older and, as the images on their signs showed, seemingly happier with U.S. policy.

In fact, spotting a likely American at the edge of the crowd, one demonstrator rushed up to give me chocolates. Then others offered me a Korean flag pin. A calendar. An offer to buy me coffee. Two more took selfies with me, all within 15 minutes.

That’s the real soul of Seoul.

This article first appeared in the Los Angeles Times. It is reprinted by permission.

.