In Venice, Artisans Preserve Ancient Forms of Art Right in Plain Sight

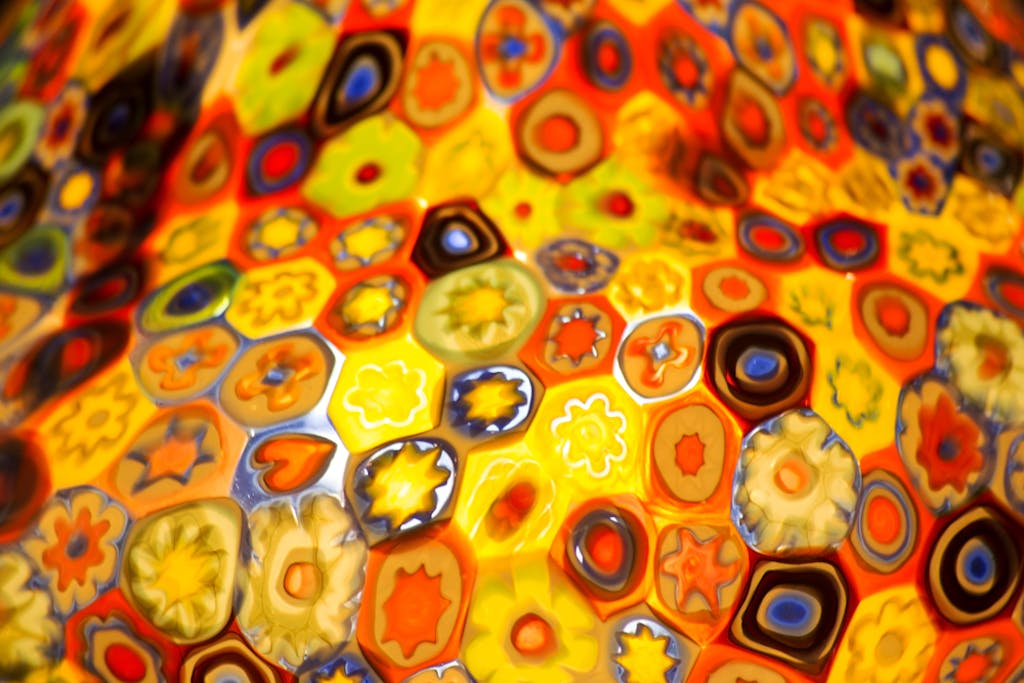

On small glass balls, turquoise swirls collide with crimson dots, violet ripples, bronze stripes, and olive motifs. This sounds like chaos of color and design. Yet these polychromatic beads are merging elegantly on a necklace, which provides a flourish to the black outfit of this jewelery’s wearer and creator, Marisa Convento.

That vibrant accessory doesn’t just represent the style of this 62-year-old Venetian woman. It also helps signify she is an impiraresse, or glass bead stringer, one of the last of a fading breed. Convento crafted the necklace from Millefiori beads, a local export that once helped the Venice Republic become a wealthy sovereign state, and even acted as currency. Now, however, the city’s glass bead art could be dying because of industrialization, rising rents and overtourism.

From the 1600s to the early 1900s, bead stringing was a common occupation in Venice, particularly for women, who did this to make beads easier for merchants to carry or to create art.

There once were hundreds of impiraresse. They enthralled visitors during the halcyon days of the Grand Tour, Convento told me when I met her in Venice. That refers to the ship journeys to France and Italy undertaken by many wealthy Europeans in the 1700s and 1800s.

Grand Tour participants often commissioned Italian artists to paint, carve or sculpt bespoke souvenirs. The impiraresse benefited from their patronage. One of Venice’s distinctive sights, during this era, was groups of women stringing beads along the city’s narrow calli streets, Convento explained.

They gathered to hone their craft near the busy quays of Castello, the largest of Venice’s six sestieri (neighborhoods). With nimble fingers, they skilfully threaded glass beads on to cotton strings. Impiraresse would store thousands of beads, created on the Venetian island of Murano, in a 2-foot-long wooden tray, a version of which Convento still uses.

Did you know that Venice’s glass bead jewelry has earned protection as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage property?

For most of these artisans, speed was paramount. They were paid by the bead, so the faster they strung the quicker they earned. This monotonous style of bead stringing disappeared long ago. Now the impiraresse rise or fall on the strength of their artistic flair.

“That kind of mere stringing of beads in bundles of standardized length and number of strings, for their shipment all around the world, is no longer required in our industrialized days,” Convento tells me. “Gradually the stringing techniques have evolved into more creative making skills – self-produced design pieces ranging from embroidery to beaded flowers, jewelry or home decor.”

Only a few dozen impiraresse remain, says Convento, who helped spearhead the recent, successful push for Venice’s glass bead jewellery to earn protection as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage property. To showcase this ancient art form, she invited me into her workshop and store, called Venetian Dreams.

It stocks Murano bead bracelets, brooches and earrings. Her specialty is colorful necklaces like the one she wears, named tutti-frutti, a vibrant blend of contrasting beads. Venetian Dreams has a glorious perch in the Dorsoduro area, overlooking Rio de San Vio, the narrow waterway that connects the famed Grand Canal with the even-wider Giudecca Canal.

This neighborhood brims with creative output. Convento’s neighbors include the iconic Gallerie dell’Accademia art museum, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection and the Squero di San Trovaso, a historic shipyard home to Venice’s last gondola craftsmen.

That latter art form is withering because of the complexity and physicality of handmaking gondolas. Bead stringing, meanwhile, was initially weakened by industrialization. Factories began to produce bead designs so cheaply and swiftly that the impiraresse struggled to compete.

Then they were hindered by the “heavy pressure of mass tourism,” Convento says. Although Venice is proud of its traditions, it’s become more inhospitable for traditional artisans. Convento has watched hundreds of small businesses gradually replaced by generic shops selling fast food, ice cream and cheap souvenirs.

Tourists usually make only short visits to Venice, she says. Many have neither the time nor the inclination to engage deeply with its artistic heritage. “(Most) end up buying the cheapest and easiest items – just simply grabbing something while in Venice, rather that something really made in Venice,” Convento says, with an air of resignation.

Rampant tourism also has propelled the price of Venice real estate. Pre-pandemic, Venice received 20 million visitors annually, compared with its100,000 residents. To accommodate this influx, more buildings have been taken over by tourism businesses, driving up rents. As a result Convento tells me, many artisans can’t afford to run their own workshops.

She survives, in part, thanks to financial support from the Italian government, because of her role with an endangered artform. Impiraresse and gondola makers are among a slew of Venetian artisans slowly vanishing…as are authentic gold leaf makers.

After I met Convento, I wandered a labyrinth of alleys in the Cannaregio district to find Berta Battiloro. This family business is the last Venice studio that still handcrafts gold leaf, used to decorate the city’s churches. Its owner, Sabrina Berta, tells me she is hopeful their art form will persist. But she cannot be sure .

Working together in Venice aims to strengthen artisans’ futures

Keen to avoid a similar predicament, the impiraresse have banded together, Convento says. They formed the Committee for the Safeguarding of the Art of Glass Beads of Venice, of which she is vice president. This group has more than 100 members from the city’s glass bead industry, including maestri vetrai master glassmakers, molatori bead cutters and polishers, and the impiraresse.

The committee successfully lobbied for UNESCO listing, which acknowledges the heritage of bead stringing in both Italy and France. This was a major boost for the impiraresse, increasing their profile and prestige. Convento and her colleagues are trying to seize this momentum.

In small workshops across Venice, they are armed with traditional techniques, modern designs, and trays of colorful Millefiori beads. Four hundred years after they became a fixture of Venice, the impiraresse are resilient, optimistic and prolific. Their luminous creations continue to shimmer in shop windows alongside the canals, churches and piazzas of this Italian wonderland.

Authentic artisan shopping in Venice

On your next trip to Venice, consider stopping in at some of our favorite artisan shops in the city:

Marisa Convento’s Venetian Dreams bead stringing (Dorsoduro)

Berta Battiloro’s gold leaf (Cannaregio)

Squero di San Trovaso gondola craftsmen (Dorsoduro)

Murano Vitrum glassware (San Marco)

Martina Vidal Burano lace and linens (Burano)